-

© Contributor : Latifa Bieloe, palabresintellectuelles@gmail.com

- 13 Mar 2025 10:09:07

- |

- 4875

- |

CAMEROUN :: My Grandfather’s Will : An Interview with Daniel Nadjiber :: CAMEROON

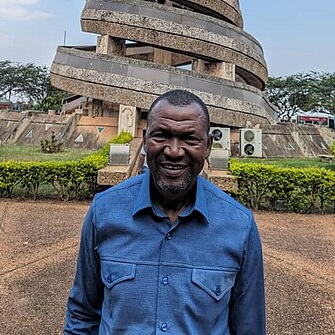

Historians taught us that some books have generated, or at least helped to inspire revolutions. Uncle Tom's Cabin, the famous Harriet Beecher Stowe's novel, just to name one, is said to have paved the way to 1861-1865 Civil War that resulted to the abolition of slavery in the territory of United States of America, under President Abraham Lincoln. Le testament de mon grand-père (My grandfather's will), a work just signed by Daniel Nadjiber, although modest, is also devoted to the liberation of a crying people. It evokes a longing and a call for justice for the Mbum people. Thank God, author Daniel Nadjiber made himself available to tell us more about this emergency situation. Latifa Bieloe, a member of the Collectif Readind is so Bookul is discussing with Daniel Nadjiber.

“The Mbum people are a people thirsty for justice,” it's written in an article dedicated to your work. The text in question is available online under the title “S'opposer pour exister : Le Testament du grand-père de Nadjiber Daniel.” The abuses of power and authority you describe in your book seem straight out of a history book; yet you persist in this accusation, according to which the Mbum remain victims of torture and barbaric abuse perpetrated against them by the executioners of the Fulani royal family. You even find it entirely justified to use harsh words like “slavery” and “genocide.” How can one explain that the rest of the World, starting with the rest of the Country, namely the Deep South of Cameroon, is so poorly informed about this unfortunate reality? And yet local NGOs and other human rights organizations make such a fuss about less serious incidents?

Thank you for giving me the opportunity to speak out about the multifaceted abuses and injustices suffered by the Mbum in Cameroon. All the facts described in my work ("Le testament de mon grand-père") are real and softened so as not to frighten the reader. If some Cameroonians in the Deep South of Cameroon pretend to ignore this problem, I would say it is out of fear of reprisals, by simple hypocrisy, or complicit silence, since L'Œil du Sahel, a smart newspaper renowned for its investigations and research based on the northern regions, has covered this issue on many occasions, as have other audiovisual and print media. Many NGOs, often in collusion with administrative authorities, prefer to remain silent rather than face the wrath of the all-powerful "Lamido," closely linked to Etoudi's power, who made him the second-largest figure in the Cameroonian Senate and president of the Senate Human Rights Commission. The Touboro Youth Collective for Development wrote to the National Human Rights Commission you refer to several times, but has received no response. It's a total blackout. As if Mayo-Rey weren't an integral part of Cameroon; it rather looks like the private property of some individual. Having noted the proximity of the Garoua regional human rights office with the Lamidat of Rey-Bouba, we had previously contacted officials at the National Human Rights Commission headquarters in Yaoundé to seek more objectivity, but were given promises without follow-up. Even worse, we don't belong to the wealthy class that has the financial means to commission media advertorials about the situation of slavery and blatant injustice we experience in Mayo-Rey, on plain view of everyone.

In your book, you say that "the Indigenous peoples of Mayo-Rey deserve material and moral compensations for having been victims of stigmatization and modern slavery." What do you mean by "material compensations"?

The indigenous peoples of Mayo-Rey, and the Mbum in particular, have suffered enormous stigmatization, discrimination, injustices of all kinds, and even cultural genocide. Because young Mbum have been systematically excluded from the education system through a cleverly orchestrated strategy to delay their access to major vocational schools. Well-oiled strategies have also been implemented to prevent these people from speaking their language, practicing their customs and traditions, including traditional initiation rites, agrarian rites, cultural festivals, and so on. Evidence of this is that in the entire Touboro district, which covers an area of 16,610 km2, there is no traditional chief recognized by the administration. However, in administrative practice, when Ministers make official visits to the Regions and the Interior, they only grant audiences to high-ranking traditional chiefs. Consequently, the Mbum are excluded from consultations and decision-making regarding the functioning and management of the country. Decades of unpaid forced labor on the Lamido plantations and illegal taxes have impoverished the Mbum people, making them uncompetitive compared to others today. The Lamibés have taken over strategic locations throughout Mbum territory and leased them to telecommunications operators.

The State, through the Southeast Benoué (SEB) project, funded by donors and implemented by SODECOTON, has also appropriated our lands to settle more than 10,000 families (climate refugees) from the far north of Cameroon without any compensation.

Robbed of their livelihoods and educationally backward, the Mbum feel wronged, abandoned, and frustrated at every level. They want their tormentors to acknowledge the harm they made them suffer. The World is changing at a dizzying speed, and the tormentors of this people must apologize and offer material compensations, similar to the Marshall Plan in Europe after World War II. This will be an important step toward social peace coexistence and living together.

Under the right to self-determination, would it be conceivable that the Mbum peoples could decide not to submit to the Fulani kingship any longer, through a referendum, for instance?

This will be a very good opportunity for the Mbum, Dii, Gbaya, Laka, Lamé, Dama, Mono, and other peoples living in the Mayo-Rey department, whose rights are unfortunately violated with the complicity of public authorities. In southern Cameroon, the Traditional Chief is the spiritual leader of a homogeneous group, but in northern Cameroon, the Fulani Traditional Chiefs were imposed as Traditional Chiefs of other ethnic groups, undoubtedly due to Cameroon's first President, who was Fulani by origin and culture. In our view, the Mbum people are dying in the era of globalization, where all peoples are immersed in cultural and civilizational competition. The Mbum therefore cannot have the necessary elements and weapons to confront the globalization of culture. If Decree No. 77/245 of July 15, 1977, on the organization of traditional chiefdoms is implemented, a referendum will not be necessary.

On page 56 of your book, you deplore the inhumane conditions of detention in the Lamidat prisons. Is it legally permissible for traditional authorities to build and control their own jails?

This is a clear violation of the law. No individual or private organization, not even a powerful chiefdom, has the right to have a prison outside the State. Mayo-Rey is a lawless department. This is a sad fact that was experienced by the young people of Touboro in 2011 and that other residents of Mayo-Rey continue to experience to this day. The current Lamido of Ngaoundéré is the only one, to the best of my knowledge, that has transformed the traditional chiefdom prison into a care and vocational training center. The other traditional chiefdoms in the Far North unfortunately retain these tools of torture and slavery.

Why did you wait so long to publish your first book, which, moreover, deals with a problem whose "urgency is acute" (in your words). Given the fact that you've been in publishing for several years now?

You're right. I've been in publishing since 2004 as an employee in another structure with no real decision-making power over manuscripts selection, and I didn't have time to gather the data necessary for this work. But don't they say, "Better late than never?" The book is now available to the public, so you can experience firsthand the harsh and unforgiving realities that the Mbum and the indigenous peoples of Mayo Rey have been trough from almost the first half of the 19th century. And the situation has worsened with Cameroon's return to political pluralism and democratic openness.

The second part of the work contains "21 keys," in this case, 21 proverbs that open the doors to the knowledge and wisdom of the Mbum people. What would be the "key to success," precisely, according to your grandfather's teachings, in an age where everything is for sale (including diplomas); where everything can be bought, in cash or in kind; where meritocracy is no longer the main criterion for social success?

Success among the Mbum is a set of actions and decisions that must be taken to achieve a goal at a given time. Mastering the 21 keys will allow you to make good decisions in a given situation and take appropriate action to face challenges and achieve results. I invite all those interested in Africa in general and the Mbum people in particular to read this book to be better prepared to face current realities.

Could you tell us a few words about the culture of the Mbum people, whose merits some authors (including yourself) have praised?

It's not that simple, to present Mbum culture in just two words. What we should consider is the diversity of their art and culture, their pharmacopoeia, and their formative pedagogy through mentoring and induction of young people and youth to prepare them for future socio-professional integration.

You've been an editor in Cameroon since 2012. How is publishing and book industry in general? Do you feel things are moving forward in your country?

In 2004, the book industry in Cameroon had just ten publishing houses specializing in general literature, theological works, and academic works. The textbook market was 95.4% controlled by Western multinationals. I had presented the analysis of the official list in a local newspaper to denounce the low market share held by national publishers. One of my employer's partners had requested my dismissal for communicating against his interests. Fortunately, my boss at that time protected me and encouraged me to continue my analysis. Twenty years after this episode, there are more than 418 publishing houses, and Cameroonian publishers control more than 86% of the textbook market. However, we deplore a slight change in the printing sector, dominated by Asians, who currently control almost 90% of the printing market. Overall, we can say that things are moving forward, albeit slowly, but there is a glimmer of hope.

Now that you've written your first literary work, do you plan to continue writing? If so, what topic are you planning for your next book?

Of course! Otherwise, I would be betraying my people. I intend to remain in writing to contribute to the preservation and promotion of Mbum arts and culture. In my next book, Mbum culture will confront modern culture in a dialogue between a Mbum patriarch and a literate young Mbum.

We look forward to this interesting perspective. In the meantime, we remain in solidarity with your cause, hoping that the public authorities will listen carefully to the complaints of the Mbum people. Thank you again, Mr. Nadjiber, for sharing these interesting reflections with our readers.

I'm grateful for your support.

Pour plus d'informations sur l'actualité, abonnez vous sur : notre chaîne WhatsApp

Lire aussi dans la rubrique LIVRES

Les + récents

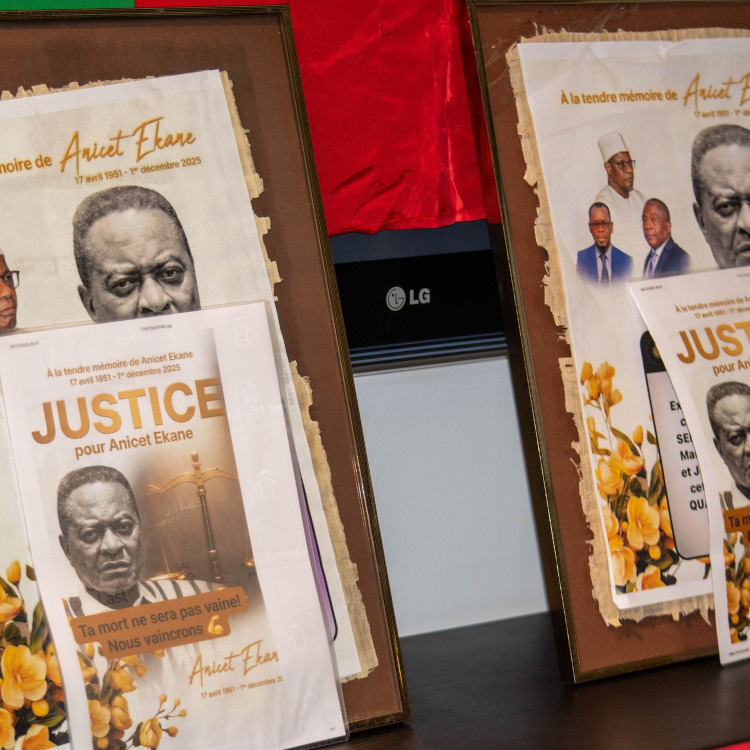

Affaire Anicet Georges Ekane : la famille réclame la dépouille au SED au Cameroun

Uranium nigérien : la France dénonce un vol et met sous pression le port de Lomé

Me Alice Nkom menacée d'arrestation : la porte-parole d'Issa Tchiroma sous pression

David Pagou : le renouveau tactique des Lions Indomptables face aux crises

Mbomgnin Gabriel: Grand notable à Fotouni et manager visionnaire à Douala

LE DéBAT

Afrique : Quel droit à l'image pour les défunts au Cameroun ?

- 17 December 2017

- /

- 220548

Vidéo de la semaine

évènement